Polish Retail tax hits EU brick wall

Prawo

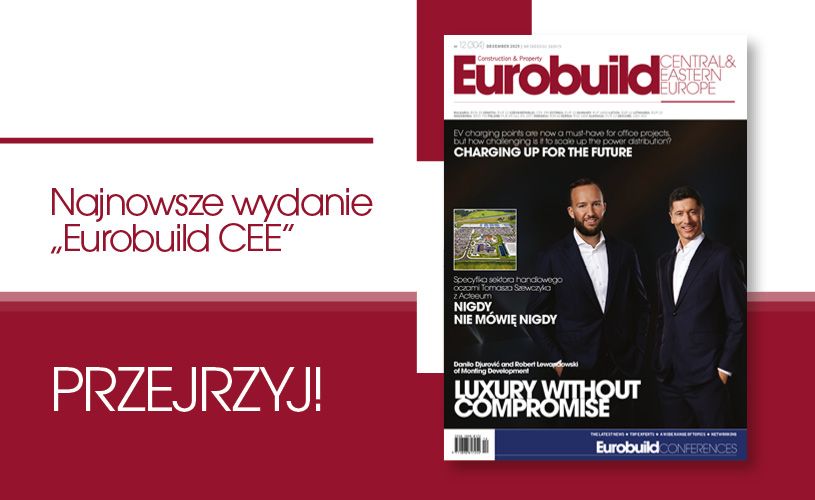

- Dostęp do magazynu EurobuildCEE online i w wersji flipbook

- Dostęp do magazynu EurobuildCEE online i w wersji flipbook

- Ekskluzywne newsy, komentarze, artykuły oraz wywiady z najważniejszymi przedstawicielami rynku i ekspertami

- Archiwum zawierające dane i informacje z rynku nieruchomości komercyjnych i budownictwa w Polsce i regionu CEE, zebrane na przestrzeni 27 lat;

- Eurojobsy

- Eurobuild FM